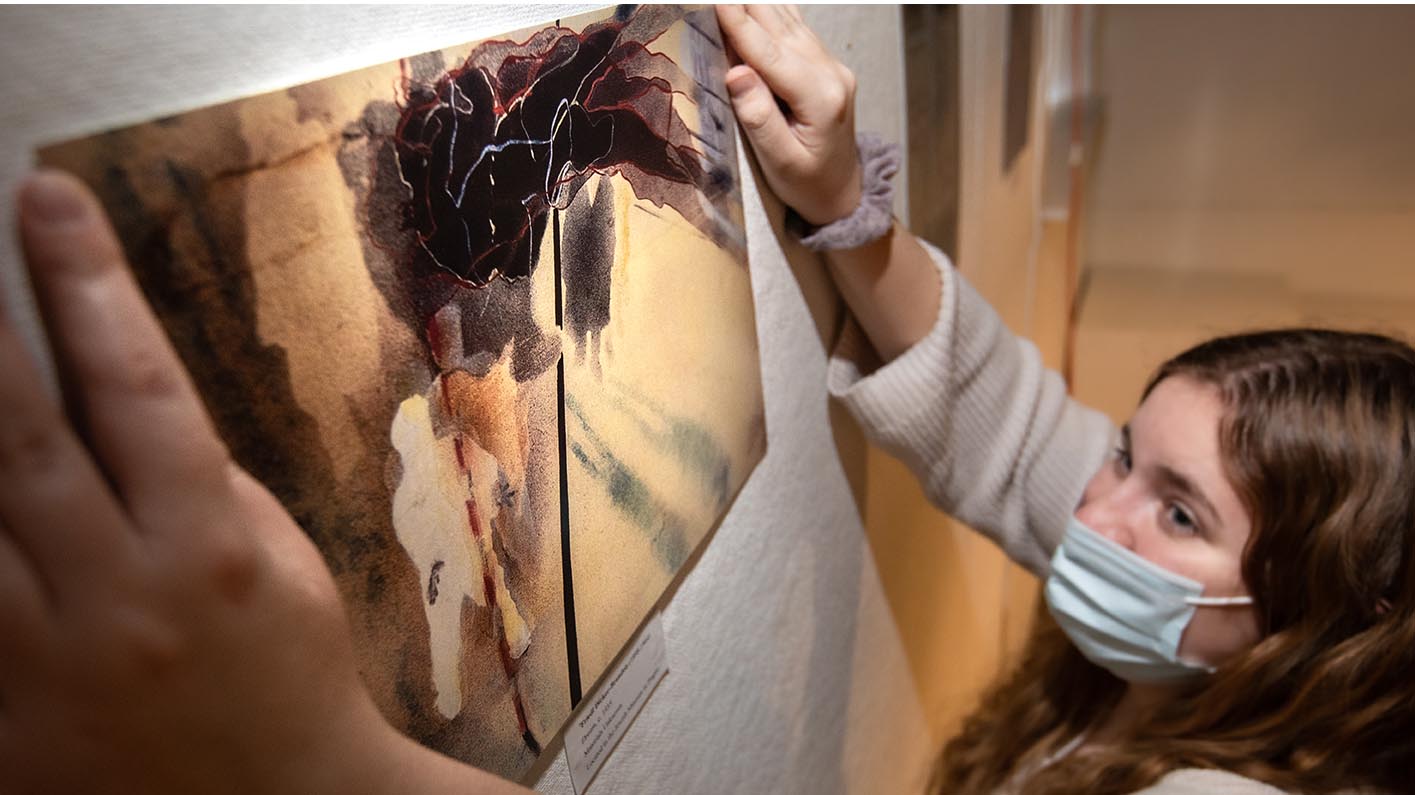

Senior Elizabeth Grassi hangs a drawing in the Vulcan Hall gallery.

Senior Elizabeth Grassi investigates an art teacher and her students who were imprisoned in a German concentration camp.

Camp Theresienstadt, or Terezin, in the Czech Republic, imprisoned thousands of Jews — including over 15,000 children — from 1941-1945.

“Despite the terrible living conditions and the constant threat of deportations,” according to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, “Theresienstadt had a highly developed cultural life.”

Jewish artists created drawings and paintings, and writers, professors, musicians and actors gave lectures, concerts and theater performances.

Thousands of children attended school, painted pictures and wrote poetry. About 90 percent of them were eventually deported and killed.

The story of one artist, Friedl Dicker-Brandeis — who survived at Terezin for two years — is the subject of an honors thesis,” Living with Hope: The Life and Story of Friedl Dicker-Brandeis,” by senior global studies major Elizabeth Grassi.

As a complement to the thesis, a selection of 31 sketches and drawings from Dicker-Brandeis and her students, compiled from books, websites and museums, will be on display in Vulcan Gallery, located in Vulcan Hall, through Nov. 16.

“This project is a recording of Friedl’s life and the impact she was able to make on thousands of children’s lives in Terezin before she was executed,” Grassi said.

Erika Taussigovå, a young Jewish girl from Prague, inspired the research project, leading Grassi to learn more about Dicker-Brandeis as her art teacher. Dr. Sean Madden, a history professor, discovered Erika’s “A World Behind Bars” during a trip to Prague.

“Nobody heard of Friedl, but look at how important she was and what she did for the people in Terezin,” Grassi said. “She brought them hope and maybe even a little bit of peace.”

“Friedl took several art classes as a child and as she grew in hopes of being an artist, but she did not look at her own classes that way,” Grassi said in her research paper. “Rather they were to encourage ‘… creativity and independence, to awaken the imagination, to strengthen the children’s powers of observation and appreciation of reality.”’

Madden and art professor Laura DeFazio advised Grassi on the project. She learned to rely on more than just the Internet and books, contacting international and local historical societies, museums and Jewish centers.

“I didn’t initially expect to get into the art portion,” she said. “But Professor DeFazio helped me learn how to analyze some of the pieces, and once I did all this research and learned so much, she mentioned an exhibit and I couldn’t let that go.”

“I think it is interesting and important that Liz, like so many of our capstone students, came to the realization that research leads and ideas, in any discipline, often results in dead ends,” Madden said. “The real essence of research is to push on, and that push is what resulted in Liz's work.”